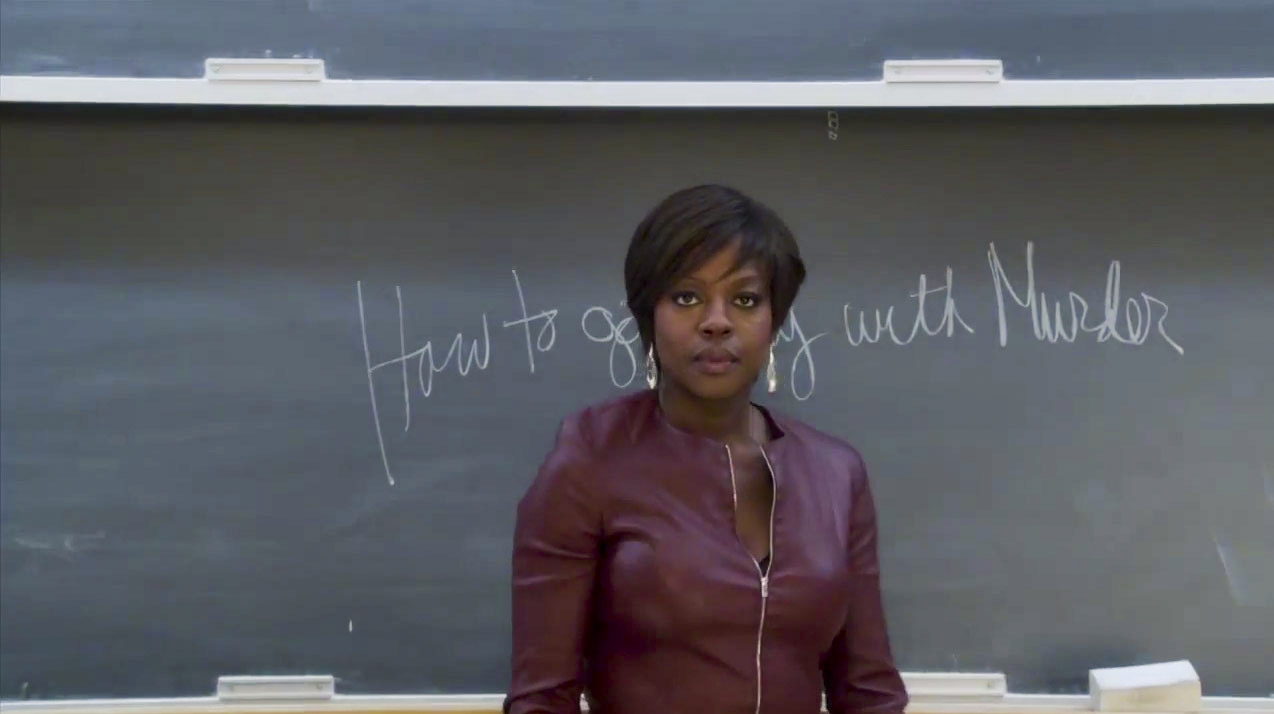

Last week there was an open discussion (okay, maybe more of an argument) over New York Times writer Alessandra Stanley’s reference* to Viola Davis in Shonda Rhimes’ new show, “How To Get Away With Murder”: “Ignoring the narrow beauty standards some African-American women are held to, Ms. Rhimes chose a performer who is older, darker-skinned and less classically beautiful than Ms. Washington” (here referring to Kerry Washington, the actor who plays Olivia Pope, the lead character in “Scandal”, one of Ms. Rhimes’ other shows.

There are several problems with Ms. Stanley’s article, and she angered women in general and black women especially by seeming to allow for the “classical” standard of beauty to carry weight it ought to have been forced to drop by now. Ironically, she also notes that “Even now, six years into the Obama presidency, race remains a sensitive, incendiary issue not only in Ferguson, Mo., but also just about everywhere…”

Well, yes. There are significant issues of race, and they’ve been debated thoroughly since the piece was published. But there are issues of gender and aesthetics, too, and I want to explore those for a moment here. Culture asserts capricious and rigid demands for physical attractiveness at women of every ethnicity. Viola Davis is a gorgeous and gifted and incredibly smart actor. I can’t even imagine that someone would consider her less than utterly beautiful. But Ms. Davis, along with plenty of others – Christine Baranski, Maya Rudolph, Jill Scott, Melissa McCarthy, Mariska Hargitay, Misty Copeland – have all had it said of them, in so many words, that they are “not classically beautiful”.

But who says? Who says they’re not beautiful? What is “classical” about beauty? And why is that even a thing?

Appearance requirements for men have become more stringent, too, in the glare of HD cameras and ubiquitous media and publicity. But many “not classically handsome” men actors get amazing roles and lots of opportunities: Steve Buscemi, Philip Hoffman, Sean Penn, Will Farrell, Samuel Jackson, Jim Gandolfini… (I could go on for a good while) have all been offered great roles and made fantastic movies.

Why is it so much easier for men to defy and succeed well beyond the caprice of ‘standards’ – attractiveness, along with height, age, weight, muscularity, and even hairlines – than it is for women?

The disparate dynamic is certainly worse for women of color, at whom our culture, wandering between ignorance, xenophobia, and guilt, flings its critiques with a freer tongue and lower inhibition. Women in general seem to be more profoundly subject to limits and stereotypes. And substantial roles for women performers are thin and rare.

Movies, and increasingly, stage productions, are mostly made to reinforce what everyone already thinks, not to challenge and expand worldview. Sad. True. Producers stack profits by reassuring people they are right. Entertainment works by affirmation, by engineering experiences in which the audience feels it is in control of a good world that reinforces everything they already thought was true. People enter theatres with a preset notion of beauty; no studio is going to buck that standard by challenging patrons to see differently. They’re not in it to speak truth; they’re in it to make money.

Which makes this beauty standards thing yet worse. Who decides who’s beautiful and not? Why does anyone think they need to decide? And especially, what prompts us (hint: the Fall) to think we have a right, and even duty, to confine women to a rigid range of acceptable appearances, and to snub those who don’t fit? I want Viola to be seen as a fantastic actor, and to be appreciated as a beautiful, vital woman with something to offer the world. I’m hoping.

*The NYT article I quoted can be found at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/21/arts/television/viola-davis-plays-shonda-rhimess-latest-tough-heroine.html?_r=1